ETFs in brief

Exchange traded funds (ETFs) contain a basket of different assets, such as stocks and bonds, and trade on an exchange – much like a stock. They are an easy route to investing in a pool of assets without having to buy each one individually. This means they are a highly efficient way for investors to build an investment portfolio that is diversified across different regions and asset classes. A globally diversified, multi-asset, ETF-based portfolio can provide exposure to thousands of underlying investments.

Different types of investments include:

ETFs can cover areas such as: | Example |

|---|---|

Asset classes | Government bonds |

Specific stock market indices | FTSE 100 |

Regions | Europe |

Sectors | Technology |

Market segments | Small-cap stocks |

Themes | Renewable energy |

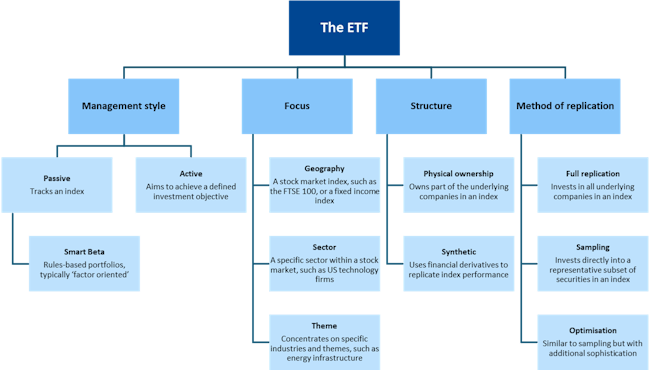

The ETF market is vast, with around 12,400 ETFs available worldwide*. Different combinations of management style, market exposure, structure and method of replication are available across markets – all of which we discuss in detail below.

ETFs can capture broad swathes of financial markets, from tracking the Russell 3000 – which aims to capture the vast majority of the US stock market – to niche markets that are far more illiquid. The below chart aims to capture some of the different characteristics of ETFs.

Source: J.P. Morgan Personal Investing. ‘Factor oriented’ Smart Beta ETFs select and weight their investments based on specific investment factors such as whether an investment appears undervalued relative to the market, or has higher growth prospects.

ETF management styles

At the headline level, one key distinction is whether the ETF is managed with a ‘passive’ or an ‘active’ investment strategy. It is important to note that ETF simply means exchange traded fund, and is not synonymous with index tracking. The ETF is the vehicle within which different strategies can be used to achieve different investment objectives.

While passive funds have, historically, been the predominant type of ETF, actively managed ETFs are becoming increasingly popular. J.P. Morgan Asset Management reports that, in the US, the amount of money flowing into active ETFs in 2024 ($296.7 billion) was 11 times higher than it was only five years previously in 2019 ($26.8 billion).

J.P. Morgan Asset Management is an industry leader in the space, with 40 available active ETFs in Europe. As at October 2025, assets under management totalled over $42 billion in active UCITS ETFs – ETFs that are compliant with the European Union's Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) regulatory framework.

'Passive' ETFs

These ETFs aim to track the performance of a specific market index. Being ‘passive’ means there is a clear benchmark, which is explicitly defined and published, that the ETF is tracking and doesn’t aim to beat by deviating from it. It gives the investor exposure to whichever index, sector or theme the ETF is tracking.

Example:

- An index might consist of 100 stocks with total market capitalisation – the combined total value of all constituent companies’ shares – of £100 billion.

- If Company A has a market capitalisation of £5 billion and is the most valuable company in the index, it would account for 5% of the index’s value. If Company B is the smallest with a market capitalisation of £500 million, it would account for 0.5% of the index.

- An ETF tracking that index using the ‘full replication’ method would hold investments in all 100 companies in the same proportion as their index weighting.

- The ETF would be 5% allocated to Company A, 0.5% allocated to Company B, with all remaining 98 companies invested in on the same basis: how valuable they are as a proportion of the whole index.

This method is called ‘full replication’, and involves the ETF physically investing in all constituent members of the index that it is aiming to track. This is typical for highly liquid markets, where buying and selling of underlying securities is straightforward and cost effective.

There are other ways that passive ETFs are set up. The investment objectives of the ETF and the characteristics of the market it is tracking will differ, and the replication method used will vary on this basis. Some are more suited to specific market characteristics, such as for illiquid markets, as we discuss later. Some ETFs use a combination of methods in a ‘hybrid’ approach.

Smart Beta ETFs

These are slightly different in that they follow a rules-based, systematic approach to choosing stocks from a particular index. They are often constructed to deal with specific inadequacies or excessive bias in some markets. They still track an index, but weightings are determined by a combination of other fundamental factors, such as total earnings, profits, revenue, or dividend payouts. This is opposed to simply using market capitalisation to determine weights. However, it is important to note that they remain rules-based in their approach.

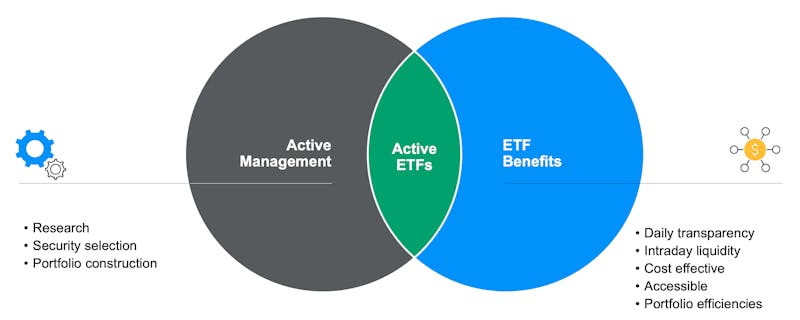

'Active' ETFs

Active ETFs do not track the performance of a reference index by investing in the index’s underlying constituents on a market capitalisation-weighted basis, like many passive ETFs do. Instead, the fund management team of an actively-managed ETF will aim to meet specific investment objectives by making ‘active’ investment decisions. The investment objective can vary but it is generally to attain a defined outcome, for example: outperforming a reference index, or generating a certain level of income. They combine the potential benefits of active management, such as the security selection experience of investment experts, with the many benefits that the ETF investment vehicle brings.

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s Guide to ETFs, data as at 31 July 2025. For illustrative purposes only.

How active ETFs work

As noted, an objective of an active ETF can be to outperform a reference index. Therefore, rather than holding investments at a proportional weighting of the index, as many passive ETFs tracking an index would, the portfolio management team uses their research and investment expertise to take a distinct view. This may see the weighting of a stock or a sector be slightly higher or lower than the index, depending on whether they have a more positive or negative viewpoint.

Relative to passive ETFs, active ETFs introduce higher tracking error risk. Tracking error is a financial metric that measures how well the ETF replicates the performance of the reference index. Given passive ETFs' goal of replicating the performance of a reference index, a low tracking error is typically targeted. For active ETFs, there is naturally the potential for higher tracking error, but alongside this they can help investors to gain ‘Alpha’ (risk-adjusted outperformance) in a portfolio alongside core passive holdings. Active ETFs can also be used for tactical allocations at different times through the market cycle.

Other replication methods

Sampling and optimisation

These two techniques involve investing directly into a representative subset of securities that closely match an index’s risk and return characteristics. They fall under the ‘physical’ category, as explained below, as the full replication method does.

Sampling is often used in the fixed income space and is suited to particularly large markets where there may be thousands of constituent holdings and it may not be practical or efficient to hold all of the securities. Optimisation is similar in principle, but with added sophistication through advanced quantitative modelling. It can be used to replicate the performance of particularly large broad-market indices, such as for global equities, where there are a particularly large number of underlying index constituents. It can also be used for illiquid markets where full replication may be prohibitively expensive or complex, or where there are specific constraints which need to be incorporated into the fund’s construction. It also falls under the ‘physical’ category.

Structure

Physical or Synthetic

With physical ownership, the ETF invests in an index’s underlying physical securities. For example if an index is aiming to track the FTSE 100 using the full replication method, it directly invests into each of the index’s 100 underlying companies on a market capitalisation-weighted basis.

Compared to this, synthetic ETFs do not invest in an index’s underlying physical securities. Instead, they invest in financial derivatives, specifically 'swaps', to replicate the performance of the target index. These are legal agreements between two parties: 1) the counterparty – normally a bank – and 2) the ETF provider. The counterparty agrees to deliver the return of an index to the ETF in exchange for the return generated by a basket of securities. This basket is also used as collateral to provide protection if the counterparty is unable to fulfil its obligations. Synthetic ETFs can carry some credit risk – the possibility that the counterparty is unable to fulfil its obligations – compared with physical ETFs. However, in recent years ETF providers have significantly improved the mechanism to protect themselves against this.

The method can be used where it is difficult or inefficient to invest in an index’s underlying securities, as well as for more niche markets where financial derivatives can be an efficient vehicle through which to gain exposure. The method can provide lower administration and operational costs, better replication of specific assets and can bring down the total expense ratio.

Common focuses

The ETF universe is extensive, with continuous innovation seeing the expansion of the number and type of funds available. Some common types of market exposure that ETFs capture include:

- Geography: by far the most popular type of ETFs are those tracking a large part, if not all, of an index. For example for stock markets, indices such as the S&P 500, which measures the performance of the 500 largest US companies, or the Russell 3000, which aims to measure the performance of the whole US stock market. In this instance, the underlying stocks are highly diversified and likely to encompass both household names and lesser-known companies from a range of industries.

- Sector: these track a particular sector, be it technology, healthcare, energy and many others. Investors may favour a sector ETF in order to benefit from the business cycle or to leverage one sector’s risk/reward characteristics. For example, the technology sector may be prone to more volatility than a traditionally stable sector like defence.

- Theme: ETFs in this area focus on long-term trends and themes. This can range from the energy transition and the infrastructure that supports it, to robotics, artificial intelligence and healthcare innovation.

* J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s Guide to ETFs, data as at 31 July 2025.

Risk warning

As with all investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down or up and you may get back less than you invest.